There was an ancient route from Kashmir to Haridwar traversing through the shivalik ranges of Jammu that brought traders, seekers and invaders to India. Haridwar is a pilgrimage town of antiquity on the bank of the Ganges, about 16 miles downstream from Rishikesh from where Beatles started their journey into meditation in the late 1960s.

While larger regions of Jammu remain insignificant in the wider milieu of India’s ancient and modern history and is known mostly to the global fraternity due to its being in the region that draws conflict between India and Pakistan, there is a piece of my family’s history that can fill in some gaps.

Somewhere in the second half of the 1800s, my great great grandfather (GGG), embarked on a journey from a village called Rampur rasool in the lower shivalik ranges of Jammu to Haridwar. In those days, I was told by my grandfather that the community would choose the strongest, well-built young men to carry over the ashes of the cremated deceased on foot to Haridwar.

Rampur rasool is about 20 miles from today’s town of Billawar, a tehsil headquarters that finds its mention in Rajtarangini, the ancient history of Kashmir by Kalhan as well as in Gulabnama, the history of Dogra ruler, Gulab Singh.

Billawar was on an important trade route from Kashmir to Haridwar–according to Al-Beruni this route passed through Pinjor (near Chandigarh), Dahmala (Nurpur), Billawar, Ladha and Rajapuri fort, before going to North through Pir Panjal pass.

About 2 miles from Billawar, there’s a river crossing point called Babre da nal, named after the Mughal ruler Babur whose one battalion faced intense infighting and bloodshed while crossing this river, while on their way to Delhi.

According to my family oral lore, GGG on community duty took this route from Billawar to Haridwar. And while returning somewhere at Patiala, when a Maharaja of the princely state of Patiala , was addressing a public gathering, a commotion broke loose threatening a stampede. GGG, a tall, well-built young man helped bring it under control and this caught Singh’s instant attention.

The Maharaja offered GGG a place in his army in the Patiala garrison and due to this his two sons were educated in Patiala. My great grandfather, Pt. Sant Ram Dogra thus did his BA from Mohindra College which was affiliated then to Calcutta University.

Dogra, a gold medalist thus became the first graduate of the Dogra state of Jammu and Kashmir. He was appointed as an assistant settlement Officer in Maharaja Pratap Singh’s reign that preceded the rule of Maharaja Hari Singh and was put on special duty to compile the customary traditions of Kashmir valley which would become the basis of a unified code later and henceforth lead to a civil law.

Codifying tribal customs

“Drawing on colonial policies in the Punjab where revenue collectors had been directed to ascertain the customary practices in each village, in 1915 Maharaja Pratap Singh appointed Pt. Sant Ram Dogra, Asst. Settlement Officer, Kashmir to prepare a consolidated code of tribal customs prevalent in the Kashmir valley,” said Chitralekha Zutshi, in the chapter “Contested Identities in the Kashmir Valley” of her book: Languages of Belonging Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir.

Dogra toured the valley “exhaustively” according to Zutshi and compiled his inquiries into “Codes and Customs of the Tribes of Kashmir” that elevated the prevailing customs of different tribes in various villages of the valley to the level of a law.

“The codification of custom was part of the movement by the state to amend, consolidate and declare laws to be administered in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which found fruition in the Sri Pratap Jammu and Kashmir Consolidation Act 1977B (1920). Based on Dogra’s code, the Sri Pratap Act, while granting primacy to Hindu and Muslim Personal Law, recognized customary laws in cases where it had altered or replaced personal law,” said Zutshi.

The cover of the personal copy of the former DC of Pulwama, of the “Code of Tribal Customs in Kashmir ” originally drawn by Pandit Sant Ram Dogra in early 1900s. The original copy of the book is hard to find these days. (From the collection of Venus Upadhayaya)

The motivation behind this codification in Kashmir was the need for an assessment of land holding rights because the agricultural classes applied customary law in matters of land inheritance and land division, according to Zutshi.

Sant Ram Dogra was killed on his way home to see his newborn son, my grandfather who was just nine months old then. Based on grandfather’s age records, my estimates say he died in 1918 or 1919.

Riding his newly bought bicycle he was run over by his own horse buggy, most likely on that same route that connected Kashmir with Billawar. My grandfather who unlike his father could never go to school repeated this story many times to share his pathos of never being able to ever see his “great” father.

The perception that prevailed around was that his adversaries didn’t want him to do his work. I was told he was to compile a similar code for Jammu and Ladakh as well but my research doesn’t corroborate any such intent of Maharaja Pratap Singh.

Much of this family history was limited in my knowledge to my grand father’s stories and rest was shrouded in oblivion with our Patiala property sold decades ago, our massive home library wasted to termites and dust and Dogra’s gold medal, a piece of real gold having fallen to family feuds.

Lost in history

Codes and Customs of the Tribes of Kashmir is hard to find in print these days. I do have a soft copy preserved by an uncle abroad but during a recent trip to Kashmir I decided to search for the book in the Sri Pratap Singh Library.

I was told that the collection of antique books was lost to 2014 floods in the Srinagar valley. When I asked a young man at the front desk where I could get a copy of this book that came to be recognized as civil law in state high courts, I was told Kashmir follows “Sharia.”

This comment made me think about if Dogra’s death was linked to his high profile work and my research led me to Zutshi’s work. I don’t know if the Maharaja ordered any investigation into the case but a late historian from Jammu told me few years ago that early 1900s saw many court murders in the Dogra administration.

However the ramifications of Dogra’s work as highlighted by Zutshi, herself of Kashmiri origin, does highlight a background that demands more research.

The entire issue of dispute on Kashmir has been about land. Dogra’s work defined much that directly impacted all subjects including the very rich hindu and muslim landlords as well as powerful management of religious shrines of those days.

Zutshi writes that Dogra’s code came to be the recognized as the law in state courts, “particularly since there was no parallel body of Muslim law that ligitants could draw on.” The problem arose because Dogra’s work replaced the “ambiguities and inconsistencies that governed the lives of Kashmiris including a whole lot of disputes” by an “exact science of customary law.”

“Since Hindu and Muslim personal law could be negated if a ligitant proved the existence of a custom, the laws of religious communities often ceased to have a considerable impact on legal decisions meted out in state courts. As a result the divisions within the muslim community came into sharper focus, since customary law cut across religious boundaries, being dictated by tribe, locality, district, and so on,” said Zutshi adding that in a diverse muslim society like Kashmir it created new challenges for shrine management.

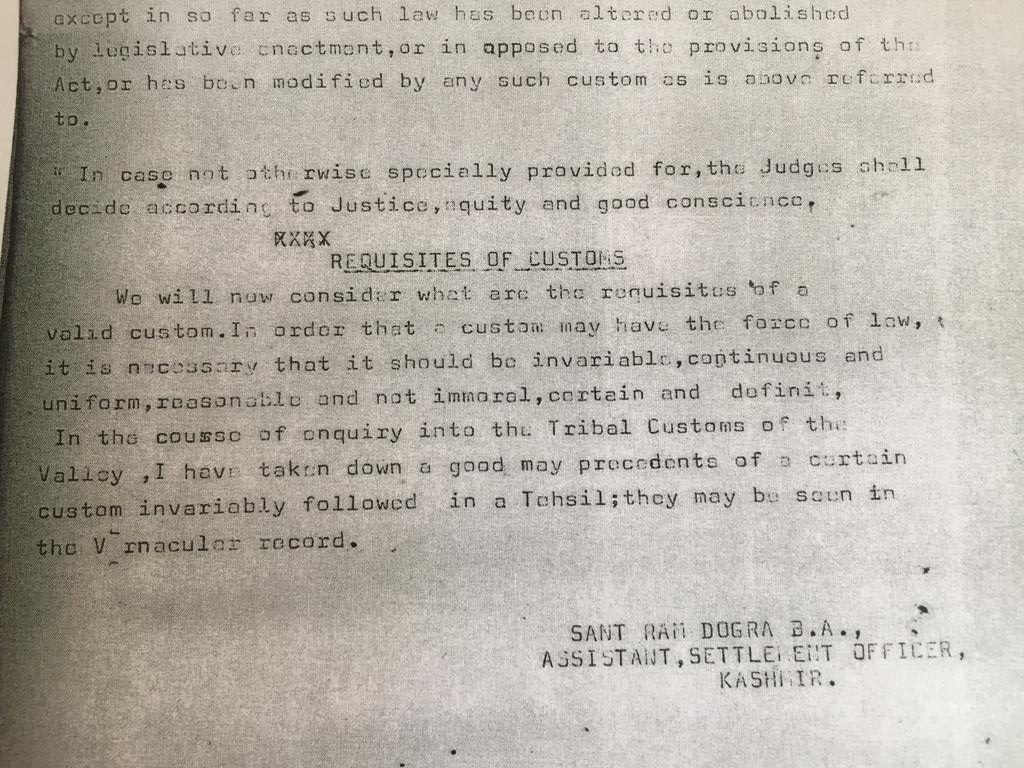

Definition of “Requisites of Customs” for it to “may have the force of law” drawn by Pandit Sant Ram Dogra, the Assistant Settlement Officer of Kashmir appointed on special duty by Maharaja Pratap Singh to codify the customs of the tribes of Kashmir in 1915. From the collection of Venus Upadhayaya.

This created immense problems because due to Dogra’s work an unwritten custom was now recorded and it had the power to be used in a court of law to bring charges against a particular shrine manager and replace him with an “amendable caretaker.”

Parallel body of Muslim law

“At a time when shrines had become the terrain for battles over influence and power, such a code only served to add fuel to the already blazing fire,” wrote Zutshi.

The only way for those critical of Dogra’s code was to bring a personal law that could be used to override the customary law but Zutshi writes this was even more dangerous because it would bring out sectarian divisions among Kashmiri muslims.

“After all if a corpus of muslim law was to be written practically for the first time, whose law would it be: Sunni or Shia, Hanafi or Ahl-i-Hadith, to name but a few divisions? These sectarian differences gradually aligned themselves along lines of division already existent in the community,” said Zutshi.

This social matrix of muslim identity in Kashmir then formed the background to the politics of Sheikh Abdullah that stormed the valley and its religious insitutions from early 1930s.

By this time Maharaja Pratap Singh’s reign had ended in 1925 leading to Maharaja Hari Singh’s that ended with accession to India in 1947.

This was also the transition period between the two world wars whence colonial powers jostled for influence leading to a wider polarity between the existing political systems and the emerging socialist cliques around the world and the Dogra kingdom wasn’t left untouched.

Meanwhile after Dogra’s death his sons rose to ranks in the tehsil but they could never rise to his intellect and his stature in the Dogra administration and with Kashmir taking precedence in the politics, my ancestral region further passed into oblivion.

Note: In the article “Small Piece of a Family’s History Could be Missing Chunk in Kashmir’s Puzzle” by Venus Upadhayaya, there was an error in seventh and eighth para–Maharaja Mohinder Singh was not the king of Patiala during the time when GGG moved to Patiala. Until the writer finds the correct Maharaja and GGG’s specific year of migration, the information is generic.

First in a series on the untold history of Jammu and Kashmir based on family history, anecdotes, cultural linkages and ancestry. Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of the media she’s attached to.