I hired a cab to the village of 95-year-old Beli Singh, a former bodyguard of Maharaja Hari Singh and also a former presidential guard during the time of India’s first President, Rajendra Prasad.

The road winding through pine forests was bad, broken at many points by the many dormant springs of these Shivalik ranges that come alive during rains. Until we reached the quaint village, where a mud house stood elegantly displaying its post-harvest tools and its mud walls merging well with nature around. For a city dweller this is an ideal holiday spot, an easy door to emptying oneself of the urban clutter.

But this illusion doesn’t befit Singh’s village’s reality. Locals tell me children have to hike for one hour, one way to a bus stop for college. The local primary school isn’t talked about with great interest. Where would the new employment be while people complain about the agricultural land losing its productivity?

Until recently these hills and its dwellers were known to the outside world for only the gods and goddesses they enshrined. A popular shrine meant a little local tourist hub and a steady income for the locals. But for the past few years, there’s been something more happening – narcotics making their way silently into these sleepy villages.

Himachal Pradesh’s drug problem is impacting my region too

A November 2022 report in The Tribune warns about increasing drug peddling involving youth into Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh from the adjoining regions of Punjab and the J&K union territory. The undercurrents are felt in my region too.

Downhill in Billawar town, the administration is now making it mandatory for all pharmacies (locally called medical shops) to install cameras to be able to nab those who sell syringes to those unauthorised. Schools are organising seminars and discussions on the topic.

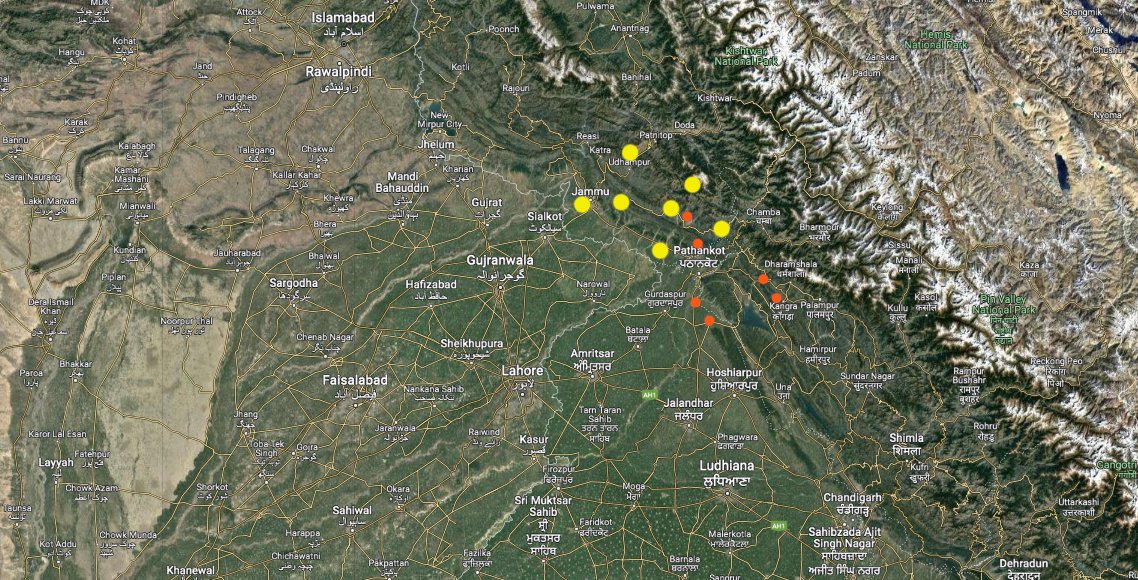

The cluster of dots represent the tri-junction between J&K, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. The orange dots show the drug-peddling spots listed in a report by The Tribune in November this year and the yellow dots show the towns listed in the recommendations for “The Shivalik National Education Route”. Credit: Venus Upadhayaya.

After the formation of the union territory, as a federally governed system started to be established, problems that went unreported suddenly seem to be visible.

More funding has started to flow into local projects; local communities are in dire need of capacity building because local implementation of national schemes and projects need that.

Local societies in my region in Jammu need hand holding support from the rest of India. If a grassroots-aware and -led policy implementation doesn’t come soon, many unscrupulous elements will start filling in the gaps. In fact they have already started emerging.

My recommendations for building a Shivalik National Educational Route

Ideally my region should be supported to catch up with what the best states in India have evolved since seven decades of independence.

This includes:

- Established and operational channels of communication between micro and macro level of policy implementation where civil society and grassroot institutions play an important role in establishing rules and laws, developing approaches and implementing policies that the legislature enacts.

- Civil society that works to uphold rule of law and regularly evaluates the development in J&K vis-a-vis the Millennium Development Goals.

- An educational ecosystem that is focused on life skills, livelihood and mental health imperatives with a focus on creating young leaders.

- Grassroots financial literacy that specifically focuses on the vulnerable population groups like women, children and people with disability.

- Build local capacities for grassroots project implementation, financial regulation.

- Create a board specifically for creating a new development model for Jammu hilly regions (based on training talent to solve problems).

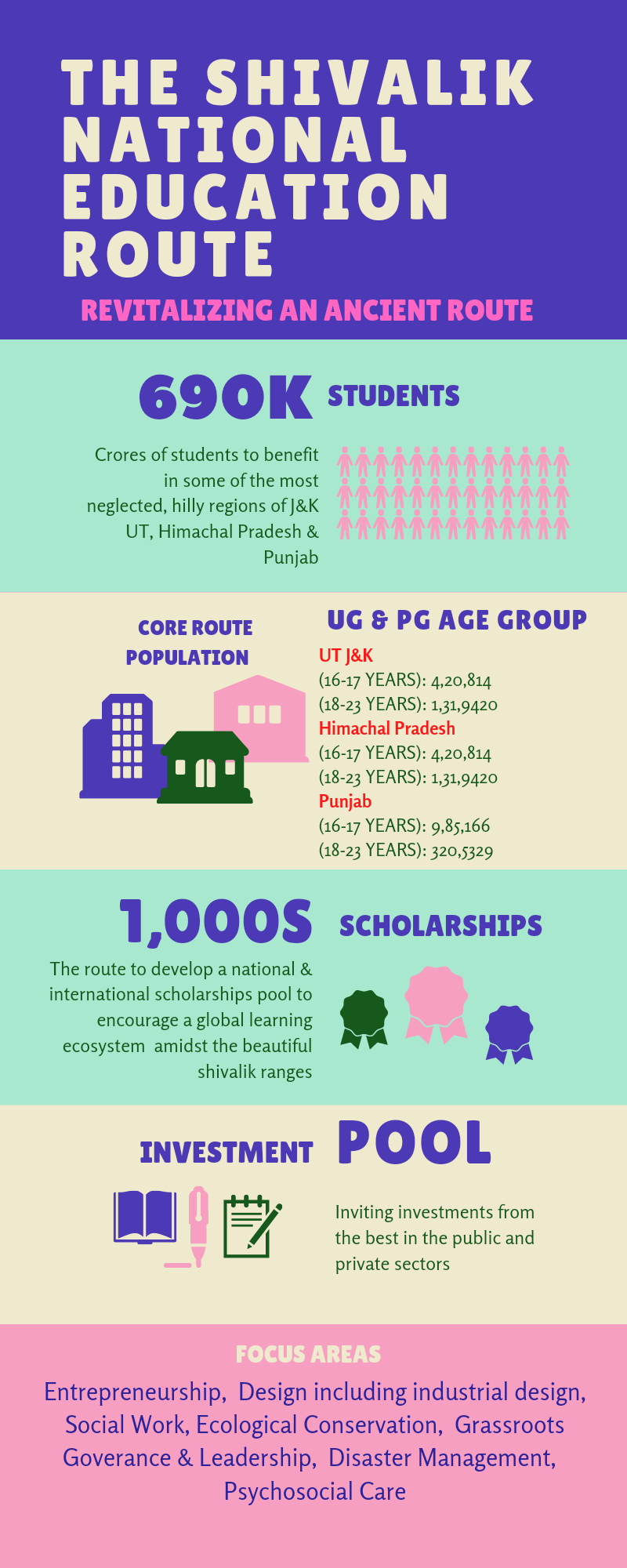

The last of these may include inviting investments for a National Educational Route (like tourism routes) that I call ‘The Shivalik National Educational Route’. This includes recommendations for the following:

- Building a National institute for Entrepreneurship at Billawar including a rural Startup Fund.

- A National Institute of Design at Basoli since Basoli is the center of pahadi (mountain-region) art.

- National Institute of Social Work at Udhampur or upgrading an existing college in order to start training local talent in models of development and it’s interventions.

- National Institute of Himalayan Studies and Ecological conservation at Mansar-Surinsar, the twin lakes that includes rare ecological resources.

- National Institute of Leadership at Kathua with special focus on building capacities at panchayats and wards in the hilly regions.

- National institute of disaster management at Jammu.

- Institute of psychosocial care intervention with intensive research focus on zero border regions and regions high on narcotics.

The lack of educational and livelihood opportunities is the main reason for impending social problems in the hills but here’s an opportunity to instead turn it into a novel region of education and livelihood opportunities.

Population and Opportunities

The Shivalik National Educational Route can act as a precursor for development, livelihood and innovation in the adjoining hilly regions of Himachal Pradesh and Punjab.

Let’s look at the 2016 Population Statistics of young people (college and university age groups) by the Ministry of Education:

Core Route UG & PG Population:

- UT J&K (16-17 years) : 420,814

- UT J&K (18-23 years): 131,9420

Beneficiaries:

- Himachal Pradesh (16-17 years): 237,212

- Himachal Pradesh (18-23 years): 735,616

- Punjab (16-17 years): 985,166

- Punjab (18-23 years): 3,205,329

In total, the Shivalik National Educational Route would be targeting a little less than 70 million. Even if it builds five million of them into skilled professionals, the development of the region would be ensured.

The word institute here is just an indicator of the intention and the aim. In design and implementation it may be called by other names. However the recommendations emphasise “national” level institutions built on the best models that invite the best talent.

An infographic highlighting the context for recommendations for a National Educational Route in the Shivalik ranges traversing J&K union territory and the adjoining Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. Credit: Venus Upadhayaya.

Crisis shouldn’t devour us

A crisis is not harmful in itself. It’s our response that determines whether it becomes a constructive or a destructive experience. A crisis can be a good thing if it becomes a context for intervention, growth and resolution. It can either become the charcoal in the furnace to smelt something more useful and purposeful, or it can remain a menace blocking our paths and threatening our purposeful existence.

On my story expedition from Kashmir to Haridwar I have been digging into much history and that will continue, however this social reality is harsher and it concerns me.

Every region has problems, that’s why we have lawmakers and policymakers to look into them, to resolve them. We have experts to dissect and decode them.

How I hope the policy and research relegation suffered by the Jammu region turns into best case stories of policy innovation and policy leadership in the coming decade! If the future belongs to Indians, let these relegated hilly regions get their due share of the new world opportunities.

Sixth in a Special Series titled ‘From Kashmir to Haridwar’ based on family history, anecdotes, cultural linkages and ancestry by journalist Venus Upadhayaya. Read the other articles here.