Lithograph of the palace of Maharaja Gulab Singh, on the banks of Tawi River, Jammu in the mid-19th century. Photo courtesy: Hardinge, Charles Stewart/Wikimedia Commons.

The history of India’s northern frontiers is about altitudes. These mountains and their passes have lured civilization as a child is lured to a game of maze and much has unfolded through them for thousands of years.

My home city Jammu, the erstwhile seat of Dogra power, stands at a fascinating junction in this game of altitudes–its fertile Indus basin at 1000 feet above sea level doesn’t abruptly lead to Himalayan peaks. The altitude from here gradually increases! If you stand at a viewpoint, you see shorter hills, then taller hills followed by higher mountains. They all appear together in the panaroma before your eyes like a multi-layered maze.

While a sea explorer wants to explore what’s beyond the horizon, a mountain explorer wants to explore what’s beyond the mountains and the only thing that leads him across are the mountain passes.

There are a-mazing panoramic views in the outskirts of Jammu city as well as on the route from “Kashmir to Haridwar.” Beyond them stand more mountains and then more and beyond those in Pakistan’s direction stand the disputed borders. They make me reflect on the 19-century history of India’s northern frontiers, particularly about the many geo-political rivalries that manifested into today’s conflicts in our lives.

Jammu for a century was the seat of the power of Dogras who ruled over the largest princely state in British India. The Dogra court was stationed in a massive palatial complex called Mubarak Mandi in downtown Jammu. I spent the first eleven years of my life in the neighborhood fortified by this complex which was itself like a maze with courtyards, tunnels and massive teak-wood doorways.

The Dogra kingdom lay right between the British Empire and the Russian Empire during the 19th century when the geo-political rivalries called the “Great Games” were at their peak between the two empires.

Yet Dogras are the least studied in any geo-political context, except for vis-a-vis the contemporary Kashmir conflict. Dogra history has turned into a fodder for the Great Game propagandists of the past and the present.

This article endeavors to understand the legacy of the Dogras who above everything were the most competent militaries of the Great Games of the treacherous trans-himalayas. They conquered territories at above 13000 feet altitude–a feat unmatched anywhere in the 19th century. Their victories were more poignant because they were fought at a time when the British and Russian empires were both intensely competing and cultivating influence in the region.

This article also seeks to ask important questions about why India’s northern borders are a sensitive military theater today. Why are the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Pakistani army stationed on massive swaths of territories originally conquered by the Dogras?

Was Mao Zeodong’s conquest of East Turkestan and Tibet not a part of the Great Games? Did the Chinese communist inherit the Great Games from their Soviet comrades who were competing for influence with the British in both what’s today Xinjiang and Tibet? Did Mao take advantage of the vacuum left after the British ouster from the Indian subcontinent?

Is Mao’s 100 years plan for China’s development intertwined with the Great Games of the past and the Great Games of the present? Did the earliest native leaders of pre-independence and post-independence India not comprehend the Great Games as well as Mao? Aren’t the Great Games continuing today albeit with different players?

Indians, and particularly Dogras are tired of the deceit of frontier propaganda. I belive these questions, if aptly attempted, can have profound impact.

Dogras and the 19th Century Great Games

Great Games were a series of geopolitical games that happened across the Himalayan and trans-himalayan mountain passes, around a massive swath of land between the British Empire and Russian empire during the 19th Century.

The Russian empire had expanded everyday at a pace of 55 square miles or 20,000 square miles per year (1) for over four centuries and the British were paranoid that the Russians would find a land route to their coveted colony of India (1). Any land route to India from Russia in the early 19th century meandered through Central Asia, Afghanistan before coming to the higher and highest altitudes of Hindu Kush, Pamirs, Karakoram and the Kailash range (Ladakh range) and finally Himalayas.

Kashmir was the first major civilizational point to the Indian mainland from across this wilderness between the British and the Russians and Peter Hopkir writes in his book, “The Great Game, on Secret Service in High Asia” that the British Intelligence was aware of at least one plan by a military general of Russian empire that involved invading India through Kashmir. In fact in the early 20th century to the British horror, Soviets entered Chitral, an area on the extreme end of British India’s northern frontiers, on the border with Afghanistan’s Wakhan corridor.

In these series of unfolding events there was one military power that went unsung in the Great Game paradigms. The Dogras, the warriors of the north western Himalayas won India’s northern territories roughly at the same time as the Russians started winning Khanates in Central Asia.

The Great Games formally started in 1838 and the Dogra military led by General Zoravar Singh won Ladakh as far as certain tracts in Kailash Mansarovar in 1834. By 1940, Maharaja Gulab Singh’s forces won Baltistan. These earliest, conclusive victories of Dogras had no colonial military support, yet they defined British boundaries and British influence.

Today large swaths of these lands militarily won by Dogras are controlled by China and Pakistan while the de-facto border tri-junction between India, China and Pakistan lies exactly in this territory of Ladakh, Gilgit and Baltistan.

The ruins of a portion of the Dogra palatial complex, called “Mubarak Mandi”. It was the dogra seat of power for over a century from 1822 to 1947. Photo courtesy: Venus Upadhayaya.

Anglo-Sikh War

Within a few years after 1822 when Gulab Singh was declared the Raja of the principality of Jammu, he managed to conquer 85 jagirs bordering the Kashmir valley (2) as a vassal of the Sikh Kingdom. Thus around the time when Central Asia was warming up to the Great Games, Gulab Singh had surrounded the Vale of Kashmir which was the first civilization point to the Indian subcontinent from Central Asia.

After Punjab fell to the British in the Anglo Sikh war of 1846, Sikh suzerainty over the Vale of Kashmir was transferred to the Dogras for 75 lakhs. At this time Satluj (2) was the outer domain of the British which was 300 miles away from Kashmir and the northern frontiers, further ahead from Kashmir weren’t feasible for the British. The geo-politics is clearly visible here on the frontier map.

While the Dogras kept winning these tough terrains of northern frontiers, the British lost many explorers, diplomats, bureaucrats and agents to the treacherous power politics of the Great Games and the paranoia about the Russians always lingered.

Around the same time as Zorawar had marched into Tibet, the British had gone further west in Afghanistan. The British Empire Army of the Indus had been totally wiped out during its humiliating retreat from Kabul.(3) Western authors wrongly compare the Dogra fate in Tibet with the British fate in Afghanistan.

They forget that while Kabul is at 5,873 feet above sea level, Mansarovar lake is 15,060 feet. They selectively closed their eyes to the fact that after Zorawar’s march into Mansarovar, the Dogras had a few territorial rights in Tibet while the British didn’t in Afghanistan.

Thus it was not a random decision, stirred by some kind of convenience that led the British to ally with the Dogras or pass on the suzerainty of the Vale of Kashmir to them. The British facilitated the creation of the princely Dogra state of Jammu and Kashmir after Gulab Singh integrated some of the most treacherous northern terrains because Dogras were the strongest and the most successful militaries of the region during the Great Game period.

What became the Dogra Kingdom ranging from Gilgit to Baltistan to Ladakh, Kashmir and Jammu lay sandwiched perfectly between the ever expanding Russian Empire and the British Empire by the mid-19th Century.

Rule over India passed on from the East India Company to the British Empire roughly at the same time as the creation of the kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir. Imagine how important the Dogras were for the protection of British interests from the Russians at that time. Would shrewd colonial rulers ally with incompetent militaries in such sensitive frontiers during Great Games!

Today the high altitude territory won by Dogra warriors of the likes of General Zoravar Singh and General Hoshiyara Singh is substantially occupied by Communist China. The entire erstwhile Dogra kingdom has turned into a military theater and a nuclear flashpoint between India and Pakistan.

All high mountain passes are militarized by the three countries while Dogras stand demeaned by the propagandists. They are either demonized or eulogized. While the truth is they were neither demons nor saints, they were a military power of the first Great Games and their history of the 19th century should be studied in this geo-political context.

A village in Pangong Tso region on the de facto border between India and China. This is the topography through which the Dogras marched to the Kailash region. (Venus Upadhayaya/June 2021)

China’s Increasing Aggression

Today China has replaced the Russians in the 19-century Great Game territory and have turned into the most aggressive expansionist power in the region. Isn’t 21st century India like the British India of 19-century facing Great Game two in its northern frontiers?

I see Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision of 2019 to bifurcate the erstwhile Dogra kingdom into two federally governed territories of: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh as a Great Game strategy. It’s Great Game two and India has started warming up to it.

So it’s high time that Indians reclaim the Dogra legacy and the Dogra’s rightful status as indomitable warriors of high altitudes.

And it’s also high time that the study of the Himalayas and the five trans-himalayan ranges of: Pamirs, Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Kailash Range and Kun Lun Shan be designated a separate legion in today’s geo-politics.

India should in its policy making designate it as a specific geo-political region because this is the fulcrum of the new Great Games.

This Great Game two region should be studied on defined parameters from an Indian perspective and a list of fresh policy indicators should be determined for policy analysis and design. In China’s pursuit of 100 years of its socialist development that’s reaching its goal by the mid-21st century this region will certainly see enhanced great games.

And India can’t escape its destiny of sharing the longest himalayan border with the PLA including the trans-himalayan borders of Ladakh. In the treacherous northern frontiers, you either conquer or you are conquered. Anything else is as blurry as today’s disputed borders–You can claim it but not control it. And the Communist Chinese are controlling it and claiming it, both!

Development perspectives have changed with Chinese translating a socialist policy of Himalayan and trans-himalayan modernization. And this will play on the global policy platforms as well in propaganda narratives.

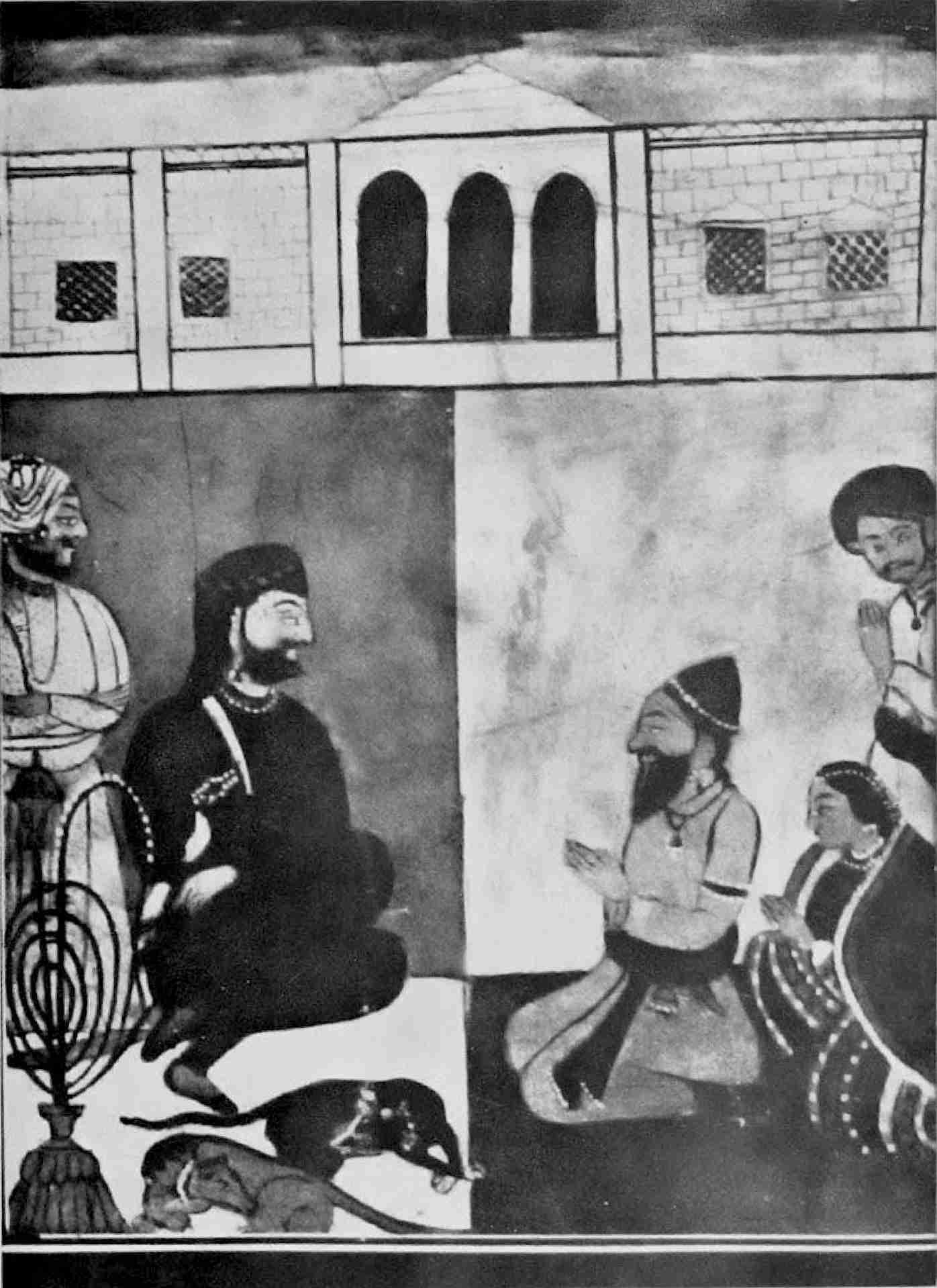

A representation of General Zorawar Singh (seated left) with the Gyalpo (King) and Gyalmo (Queen) of Ladakh following his conquest of the territory. Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliography

(1) The Great Game, on Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk

(2) India Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism, Edited by Waltraud Ernst and Biswamoy Pati

(3) Murder in the Hindu Kush: George Hayward and the Great Game by Tim Hannigan

Eighth in a Special Series titled ‘From Kashmir to Haridwar’ based on family history, anecdotes, cultural linkages and ancestry by journalist Venus Upadhayaya. Read the other articles here.